09 Nov 2016

Trump’s age of uncertainty

Donald Trump did not take long to unsettle relations with China and raise questions about a Trump administration’s commitment to a ‘one-China’ policy, a cornerstone of American diplomacy since the days of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger.

Whether the President-Elect’s phone conversation with Tsai Ing-wen, the ‘president of Taiwan’ was an intended slight to Beijing or was simply the product of diplomatic naiveté it reveals a clumsiness that does not augur well for a smooth foreign policy transition to a new administration.

" Steadiness has not characterized…Trump’s early diplomatic forays."

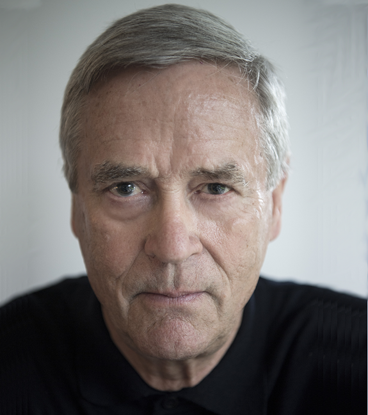

Tony Walker, Author & former editor

This was the first direct contact between a US president or president-elect and a Taiwanese leader since 1978, the year before Washington normalised relations with Beijing.

On top of unnecessarily expansive exchanges with the presidents of the Philippines, Kazakhstan and Pakistan – none of whom could be said to be paragons of Western democratic principles - Trump’s Taiwan phone call forms part of a disquieting pattern.

If the president-elect continues to indulge in actions that threaten to upend years of patient diplomacy and in the process undermine American moral authority we will find ourselves in an even bigger mess than we might have feared.

Welcome to a new age of uncertainty.

EARLY DAYS

On the other hand these are very early days. A Trump presidency in the foreign and security policy space may defy reasonably held misgivings and turn out to be more conventional than anticipated.

Much will depend on his circle of advisers and confidants - and circumstances.

If Trump persists in staking out an imperial presidency untethered from tried and tested statecraft, where steadiness is a guiding principle, a traditional American global leadership role will be undermined with unpredictable consequences.

Steadiness has not characterised, it must be said, Trump’s early diplomatic forays.

Unsurprisingly, Beijing has complained about the phone call with Taiwan’s Madam Tsai but it has done so with relative restraint - compared with what might transpire if a new administration crossed the ‘one-China’ boundaries established all those years ago in the Shanghai communique enabling a policy of “constructive ambiguity’’ towards Taiwan, in Henry Kissinger’s words.

From Australia’s perspective, hardly any development would be more disastrous than a rupture in US-China relations on an issue as sensitive as Taiwan.

No reader of this column should be in any doubt about a furious Chinese reaction should Trump disregard understandings which have enabled Beijing and Washington to manage the Taiwan issue in a way that – apart from the odd moment of tension – has avoided disruption.

While China’s official reaction to the Trump-Tsai conversation has reflected a cautious Beijing response more generally to the Trump election, Chinese commentators have felt free to lay out the consequences of any interference with the status quo.

Typical are these remarks by Shen Dingli, well-regarded professor of international relations at Fudan university in Shanghai.

“I would close our embassy in Washington and withdraw our diplomats. I would be perfectly happy to end the relationship. I don’t know how you are then going to expect China to cooperate on Iran and North Korea and climate change,” he said, adding “you are going to ask Taiwan for that!’’

PROGRESS

Shen’s reference to North Korea acknowledges recent progress made by Washington in its efforts persuade Beijing to exert pressure on Pyongyang to wind back its nuclear program, regarded as the most serious threat to peace and stability in north Asia.

Trump’s errant phone call came just days after China agreed to UN-backed sanctions against North Korea targeting its coal exports. China is the main recipient of North Korean coal.

In Canberra, a foreign policy establishment is extremely wary about a Trump presidency and the risks it poses to Australia’s own interests in the Asia Pacific and further afield.

A significant escalation of America’s engagement in the Middle East in which Canberra might be asked to do more would be an unwelcome development.

But it is concerns about China that most preoccupy policy-makers. Tensions between Washington and Beijing over trade and security with risks of a wider destabilisation in the Asia-Pacific must now be factored into any risk scenario.

At the recent national conference in Canberra of the Australian Institute of International Affairs, Peter Varghese, former head of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade had a fairly simple message for policymakers anxious about the arrival in the White House of a man whose impulses are both crude and opaque: wait and see.

“Trump appears to be a bundle of strong instincts but what we do not yet know is if he is a man of strong policy views which, taken together, form a coherent view of America’s place in the world,” Varghese said.

“And if he is such a man, how open will he be in his office to changing his view? There is a lot that hangs off the answers to these two questions.’’

That might be regarded as an understatement.

UNPREPARED

The reality is no American president in recent memory – including the former Texas governor George W. Bush - has come to elective office less prepared for the world’s most challenging job. And less constrained by what might be described as a coherent world view.

Insofar as his policy impulses can be discerned, Trump represents an amalgam of prejudices loosely conjoined by a campaign slogan to “make America great again”.

What this actually implies is unclear beyond an amorphous desire to reassert American hegemony at home and abroad.

Trump wants to restore America’s manufacturing base shredded by an inexorable process of technological change and the insistent forces of globalisation.

Whatever the President-Elect might have pledged to do about these challenges his policy prescriptions – and interventions in the market – are unlikely to reverse a long-term trend except at considerable cost to a global trading system and America’s own well-being.

Likewise his foreign policy prescriptions, as far as they can be judged by his bellicose remarks on the campaign trail, reflect raw prejudices about America’s place in the world, and threats to its leadership.

“Bombing the s*&^’’ out of ISIS might play well in Peoria but it hardly represents a coherent strategy to rid the world of the scourge of Islamic terrorism.

Nor, it might be said, does his denigration of the Iran nuclear deal – without providing a reasonable alternative – engender confidence in the ability of a Trump administration to finesse the foreign policy challenge of the moment, namely how to contain the risks of nuclear proliferation in the world’s most unstable region.

RESERVATIONS

Writing for the Project Syndicate, Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, shares the Varghese view: judgement should be reserved about a Trump administration’s foreign policy impulses.

“Campaigning and governing are two very different activities, there is no reason to assume how Trump conducted the former will dictate how he approaches the latter,’’ Haass writes.

This is true but it is also the case uncertainties about America’s trajectory under Trump come at a particularly awkward moment in post-Cold War history when US power and influence is receding relative to other players, notably China.

Haass makes the point that in a new era the “balance between global order and disorder will be determined not just by US actions but also and increasingly by what others long aligned with America are prepared to do.’’

What can be said with some conviction is the world is in for a fairly prolonged period of uncertainty during which a Trump administration seeks to get its bearings in both a fractured and fractious global environment.

And one, it must be said, that can’t be separated from economic uncertainties more or less across the board.

No longer can a China growth story be taken for granted. Nor can a continued global expansion. It would not take much to throw a fragile global the economy off course and even into a tailspin.

Australia, as Varghese points out, is particularly vulnerable because of its dependence on China which accounted for 27 percent of exports in 2015. Spreading risk in these circumstances would seem to be a priority.

Welcome to the new age of uncertainty.

Tony Walker is an author and former Washington correspondent, international editor, Middle East editor and senior political editor at The Australian Financial Review and The Financial Times.

This is the final item in a three-part series looking at a Trump environment. You can read the first item HERE and the second item HERE

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

editor's picks

28 Nov 2016

China won’t wait for Trump

Tony Walker |

21 Nov 2016