The 404 error was an obvious innovation, yet the internet you know and love wouldn't be possible without it.

It's the bane of every web surfer, the internet's version of fingernails on the chalkboard. Click almost any link that dates back to pre-2005 and brace for the inevitable: "HTTP 404 Not Found."

Anyone who's spent time near an internet connection is familiar with the 404 error, a webserver's way of saying you've reached a dead end. What's less well known is that this very error is what allowed the World Wide Web to exist in the first place.

The History of Hyperlink

Let's talk about hyperlinks. We tend to think of the vast array of linked pages we call the web as an outgrowth of internet connectivity. To put it another way: First came the communication network that allows computers to exchange data, and then on top of it we built an interconnected maze of documents, cat videos, etc. In fact, the contrary is correct. The idea of hypertext, or text with followable links to other content, predates networked computers by decades.

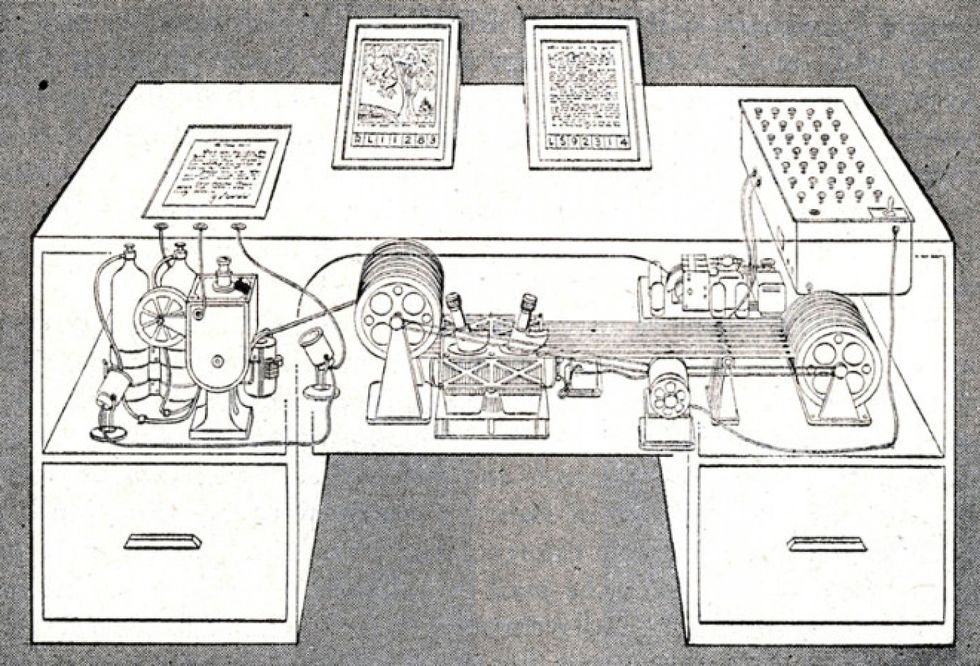

Hypertext dates back at least to 1945, when technology pioneer Vannevar Bush proposed a hypertext-augmented microfilm machine which he dubbed the "Memex." Bush envisioned a strip along the edge of the microfilm where, at the user's instruction, the memex could stamp the address code of a related film panel. Any time thereafter, someone viewing the same piece of microfilm could instantly pull up the linked panel.

Bush was so far ahead of his time that his ideas remained pie-in-the-sky dreams until the 1960's. With digital computers taking off, real hypertext soon became a reality. IT legend Ted Nelson drew on Bush's ideas for a wildly ambitious hypertext concept called Project Xanadu, though it didn't come to even partial fruition until 1998. In the late '60s, though, Nelson did co-develop a less elaborate hypertext system that supported links within a document.

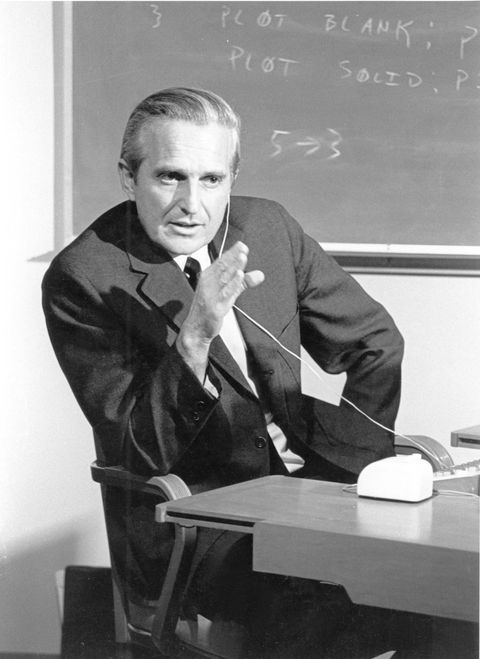

At the same time, Douglas Engelbart, one of the early greats in human-computer interaction, was working on his revolutionary NLS (oNLine System). Among NLS' many groundbreaking features was the fact that the system allowed users to jump around within a document using hyperlinks. Between the work of Nelson, Engelbart, and their successors, hypertext systems were already hanging around in the mid-1980s.

The Modern Web Takes Shape

These systems came with limitations, the biggest being that they were limited to single computers. For example, Apple's HyperCard maintained a database of note cards that could link only to other cards on the same device. But with the rise of computer networks, links from documents on one computer to documents on another were a natural extension. Even so, it wasn't until 1989 that CERN contractor Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web.

"The frustration was that there's all this unlocked potential," Berners-Lee said in 2009 during a TED talk remembering his HTTP creation. "On all these disks, there were documents. Imagine all this being part of some big virtual documentation system in the sky, say, on the internet, then life would be so much easier."

But for this idea to take root on a large scale, something was missing. That something was the 404 error.

Before Berners-Lee came along, hypertext systems typically made sure that every link led somewhere. All new links would be added to a centralized database of documents and links. If the link's target was changed or deleted, the database had to update the link accordingly.

Keeping the hyperlinks consistent was very helpful for the user. It was also easy enough to do when all the data resided on a single computer or small network. But in a large network of computers, you'd need one central authority where all documents and links would be registered. There wasn't a database in existence that could handle continuously updating every single link the world over.

For a while, this issue received little attention. Most researchers were still focused on notecards, help applications, and other small-scale systems. A few projects did allow one-way links from one machine to another without a central authority, but they still assumed that these links would be maintained as part of a team's cohesive document authoring process.

Turns out, there was a much simpler answer.

The Birth of "404 Not Found"

Berners-Lee came up with a brilliantly simple way of validating links: Don't.

In the brave new World Wide Web, the only place where information about a link lived was in the document containing the link. If the target document moved or changed, it was up to the linking document to update accordingly. Or to do nothing.

Of course, this setup means that links might point to data that didn't exist. Thus, the 404 error was born. Berners-Lee embraced the notion of missing content and just provided an official error code for when it occurred.

So where did the number 404 come from? It might sound arbitrary, but it's not. There are several dozen status codes in Berners-Lee's hypertext transfer protocol, or HTTP. Codes starting with 4 are for user-side errors, and requesting a nonexistent address—the "04" part—is just one of many ways you can screw up while browsing.

With Berners-Lee's innovation, a hypertext document could link to any other document for which it had an address. If you want to link to this article, for instance, you don't need to get my permission or coordinate with Popular Mechanics. You just do it. If we were to change the URL without setting up a redirect, or if we just deleted this article, then you'd get an error message.

That independence was one of the key factors that allowed the web to prosper. Within a few years, the world was caught in a frenzy of pages and one-way links.

In a way, the 404 did for hypertext what the zero did for math: It was obvious, but formalizing it and creating a notation revolutionized the rest of the system.

For all its greatness, this new approach also came with some problems, chiefly link rot. Over time, pages move, websites replace their content, and entire sites go offline, stranding the links that point to them. Studies have found that at least 50 percent of published links go stale within five to ten years. At least websites have made some creative attempts to entertain us with custom 404 error pages.

There are techniques to stave off link rot, whether choosing link URLs carefully or the more absolutist method of just archiving everything. But in the case of the web, the occasional 404-induced grimace is a small price to pay for a never-ending stream of news, knowledge, and cat memes.

This article was originally published on December 5, 2016. It's been updated for Internet Week, a weeklong celebration of the internet's 50th anniversary.