The startling growth of the Chinese economy has been driven by reform. Often with challenges but ultimately delivering one of the most rapid modernisations and urbanisations in history. The engine of China's reform-machine is its 300+ cities.

The Celestial City

China's cities exist in a different administrative reality than the cities most Westerners are familiar with. A successful US or Australian mayor can aspire to become a more high-profile successful mayor. In China, officials aspire to promotions into higher levels of government. To be successful, mayors compete against each other to best implement central government ambitions. Like any market, competition breeds entrepreneurship; in this case, China's best officials have proven to be remarkable policy entrepreneurs. They imitate, innovate, improvise… try anything to achieve the central government's core ambition.

For a long time, that ambition was growth. So city officials implemented markets, attracted investment, trained the labour force and invested in infrastructure. Of course the narrow growth focus also produced its own well known problems, especially over investment in capacity, whether roads, apartments or factories. Now the central government is looking at broader objectives and the best local officials are responding. They are expected to promote services, improve the environment, shift up the value chain, and create a modern (not just industrial) China.

In China, the central government announces the destination but it is up to local governments to work out how to get there. Then to do it. And for decades the destination was economic growth.

The New Chinese Urban Growth Paradigm

Recently, environment quality, inequality and the hypothesised “middle income trap" – where countries fail to make the transition from exports based on cheap labour to higher wages and a services economy - have become key concerns of the central government. Successfully improving the environment can now launch stellar careers. Inequality and fear of the middle income trap have spurred sustained pushes to increase wages from the bottom end as well as efforts to accelerate the adjustment of China's dynamic comparative advantage away from the traditional dependence upon low-wage labour.

Chinese cities are crucial to those efforts because they have extraordinary administrative and policy powers. The wealthier cities have substantial budgets and assets in their own right. Most importantly, they have authority over land distribution.

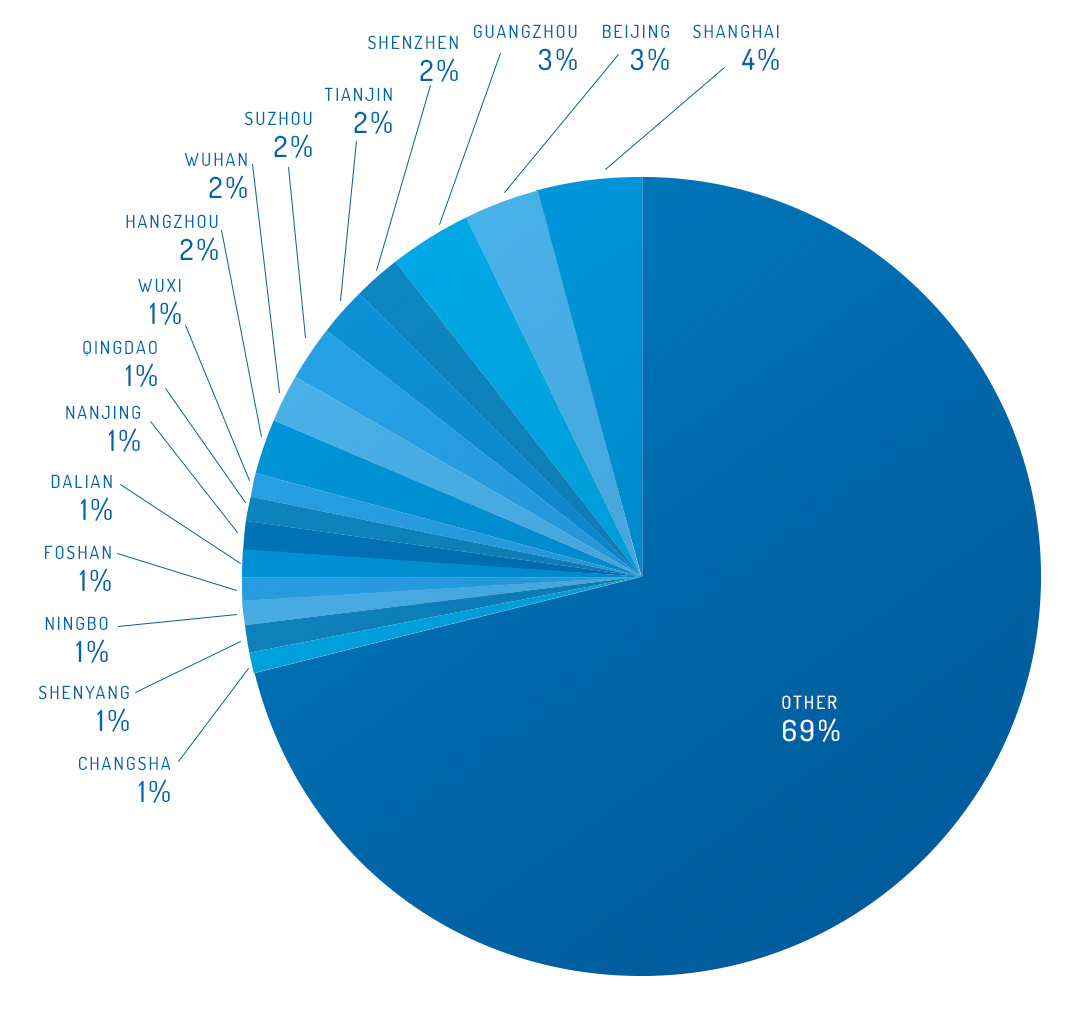

Sixteen cities stand out in China. Each has more than five million residents, from Dalian with almost six million to Shanghai with almost 24 million. Each has a local GDP greater than $US100 billion, from Changsha with $US103 billion to Shanghai with $US324 billion. And each has per capita GDP above the World Bank's high income threshold of US$12,616, from Wuhan with $US12,757 to Shenzhen with $US19,781. China's national GDP per capita is still closer to $US6,000. Together, these 16 cities produce almost a third of China's total output.

Sixteen "super" cities' share of China's GDP

Source: CEIC

The Foshan Model

Foshan's government has a relatively successful record of using its land and administrative powers to support investment that furthers economic and social objectives.

Foshan is one of China's 16 'high income' cities with more than 5 million residents, ranked 9th by GDP per capita.

Foshan, in the Pearl River Delta, is just two hours on a ferry from Hong Kong – a city with which it is deeply connected through blood and personal friendships. When Deng Xiaoping opened China, many Hong Kong business people were all too happy to help their old hometown import market institutions and foreign investment. Foshan became a pioneer of China's marketisation and industrialisation.

Bruce Lee statues at an old industrial kiln that is now a tourist attraction

Foshan is historically famous for Chinese porcelain and kung fu. Ip Man, Bruce Lee's master, was from Foshan and ceramic statues of both kung fu legends are scattered around the city. After 35 years of 17 per cent real GDP growth (a trend that stabilised rather than declined over time), Foshan ranks ninth in China by GDP per capita ($US14,647) and is now home to seven million residents, half of whome are migrant workers. It is a city of small and medium enterprises, which contribute nearly three quarters of Foshan's GDP and 95 per cent of industrial production.

But more significantly Foshan's relative success has been achieved in part by pioneering many of China's market reforms. It was an early and aggressive supporter of private land rights, supporting markets for land that were sometimes technically illegal. It pioneered many liberalising changes to the hukou system that governs Chinese people's access to public services: for instance, Foshan stopped recognising a distinction between rural and urban hukous years before that became national policy.

The Dongping bridge in Foshan

Foshan has to get creative to implement China's desired shift toward services and a modern, high tech economy. Yet Foshan is traditionally an industrial city. Just 25 minutes on the metro to Guangzhou, it has cheaper land and more space. But high-value business services prefer to operate from the Provincial capital. To succeed in China's political system, Foshan officials need to promote the services sector, regardless of the challenge of competing with Guangzhou. Their solution: don't focus on business services, instead promote industrial services.

To promote industrial services, Foshan built links with German firms and officials. With Germany, they have constructed a huge new Sino-German Industrial Services Zone covering 26 square kilometres. The zone provides facilities for major industrial projects requiring thousands of engineers, designers, programmers, scientists, and researchers. It includes two major technology research institutions: the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Foshan Industrial Technologies Institution, and aims to host around 500 technology enterprises and research institutions.

An Environmental City

Beyond space and favourable terms, Foshan has worked hard to create an urban environment where people would want to live. The zone is connected by public transport including direct links to the Foshan and Guangzhou metros, and a city-wide, free bike share program. Air and water pollution levels, once the worst in the Pear River Delta, have come way down. A huge green-belt follows the river bank for 8km – a massive public park where residents relax, play basket ball, practice tai chi and go on relatively secluded dates.

A cultural and retail district in the heart of the city, Lingnan Tiandi, has been constructed to overcome the centre-less industrial-cluster effect that was a legacy of Foshan's development. Any urban hipster would love wandering through Lingnan Tiandi's low-rise traditional architecture full of comfortable cafes, bars, restaurants, fine ceramics, local jewellery and art. Nearby are some of the city's most important cultural centres, including the Ancestral Temple, a major university, and the intersection of the cities main metro lines. Foshan, formerly a collection of industrial towns, now has a vibrant centre.

A Smart City

The Dongping river carries a large number of container ships between

Foshan and Hong Kong, facilitating Foshan's industrial exports.

Foshan's government is also experimenting with the most modern forms of e-government and 'smart services'. Sub-city districts are trialling one-stop-shops for government services. Here, residents can come to a single office that manages all public interaction with the government, from health care to taxes, disputes, and education. Terminals are available 24/7. The same integrated approach to public services is accessible through phone apps: a single app can handle almost every issue that might prompt residents to engage the local government. The one stop public service approach creates new data analytic opportunities. The service centre publicly displays data on which services are most used through which mediums. They use the data to identify where they need to improve and where to direct resources.

Smart home technology is another area where Foshan's local government is keen to see progress. At a display centre, they show off their vision of how people should be able to live in and get around their city. It may not win awards for technological innovation, but when it comes to existing technology, Foshan is looking to implement the world's newest and smartest ideas. While China is awash in liquidity and wasteful investment, Foshan appears capital starved.

Foshan's role in China's restructuring

Economists are rightly concerned about debt in China. However, there is evidence the problem is not one of too much debt so much as one of too much misallocated debt.

Foshan is a city of SMEs. In 2010, they provided three quarters of Foshan's industrial-sector employment and produced half the city's GDP. In an economic environment where excessive debt is a major concern, these firms are regularly excluded from formal capital markets. They rely mostly on self-financing or shadow banking at rates in the region of 20 per cent. Estimates in official media suggest that in 2008, when China was pushing more credit than could possibly be absorbed, there was still RMB1.2 trillion of unmet capital demand from Guangdong's SMEs.

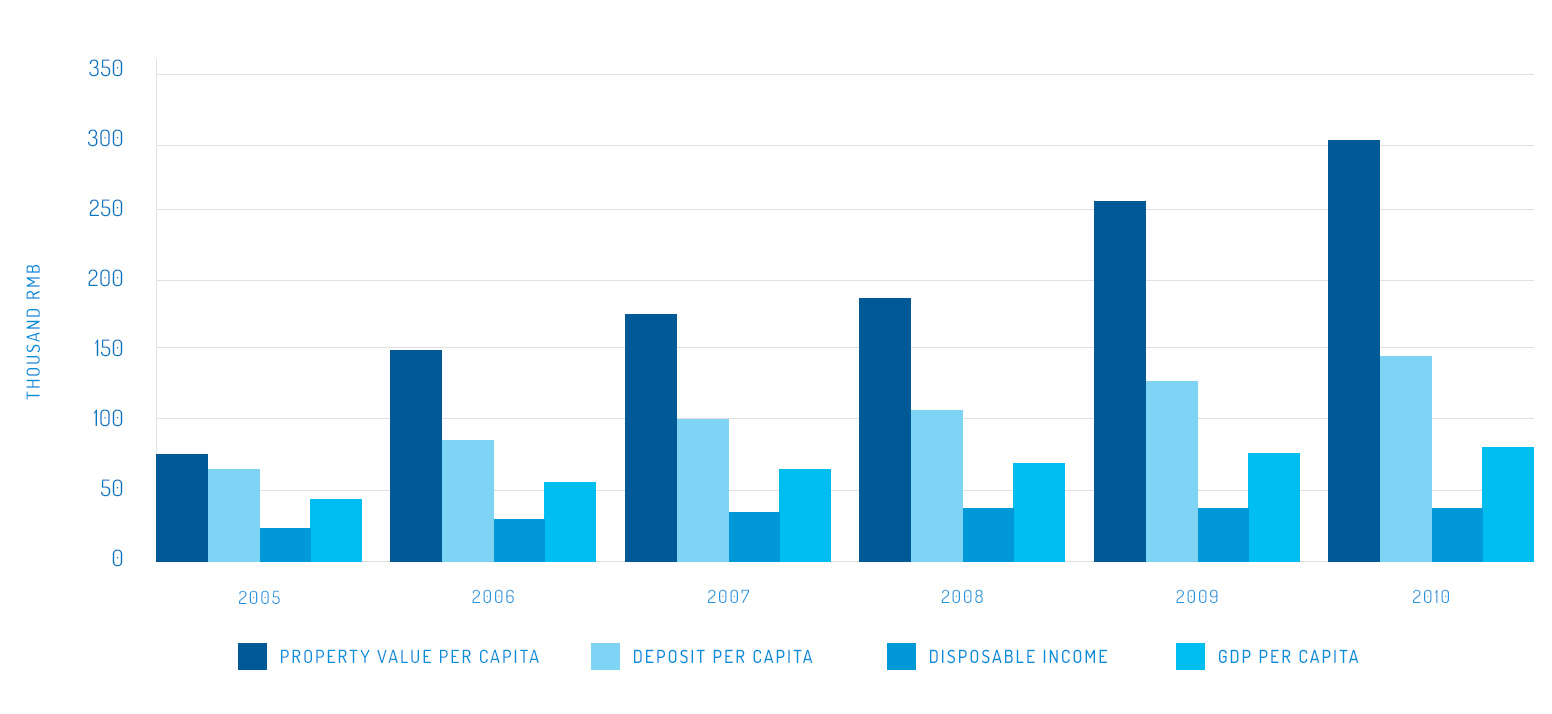

Sources of Foshan's wealth growth

Source: CEIC

The core contradiction results from China's still highly fragmented and repressed financial markets. Most banks are state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The government uses this leverage to directly influence macro-liquidity. However, banks and their executives are still subject to market forces and expected to make profits. The result is that banks direct most of their loans to SOEs, which they perceive as low risk, ignoring potentially more profitable (but risker and more effort-intensive) SMEs. Successful cities such as Foshan, with relatively few SOEs and relatively many SMEs, find China's finance markets are not serving their needs.

Reforming China's financial market is a priority. If more entrepreneurial activity and urban productivity are encouraged, it will be cities like Foshan that will flourish. Foshan could be a template for a modern Chinese metropolis.

This research is based on work done by the author with colleagues at the Fung Global Institute. A full co-authored report titled "The Foshan Story: China's evolving growth model" is available here.